A recurrent theme in the history of pen companies is a founder who got into the business by working for an existing manufacturer. The only oddity about Lamy’s start in this manner is that it comes about twenty years after prime era of such behaviour. C. Josef Lamy was a representative for Parker pens who decided to strike out on his own, establishing the Orthos Fountain Pen Factory (or, for those unintimidated by ulmauts, the Orthos Füllfederhalter-Fabrik) in Heidelberg. Doing such a thing in 1930 seems a mad move, since if there was any nation that took the Great Depression in the teeth, it was Germany. I guess the Germans were a bunch of serious writers, though, since the company appeared to thrive up to and even into the Second World War.

In 1948, the company took on the founder’s name, perhaps wanting to distance itself from the involvement of the company in arms production; this was something pen makers in England and the US also engaged in, but they had the luxury of not being on the losing and demonstrably wicked side of the conflict. I should note at this point that from 1945 to 1952, Orthos/Lamy owned the Artus pen company and operated it as a separate entity, so there is some overlap of the two (or three) companies in those years.

In 1973, the company was taken over by Manfred Lamy, C.J.’s son, who had joined it in 1957. I want to underscore the gap in the history here, as while Lamy was still doing stuff in the intervening years, what they were not doing was going off on strange tangents away from the original focus of the business. Rather, they were riding out some of the worst years for fountain pen makers in a very smart way, making writing instruments of all sorts, including what was apparently the first native German ballpoint pen, and for most levels of the market. The year I define as the start of the dark ages for fountain pens, Lamy introduced a landmark pen, the Lamy 2000, which has not been out of production since then. They seem to be proceeding in the pattern that defined the successful pen makers of the early 20th century, sticking to what they know they’re good at and treating the employees well. By way of example, in 1989 they brought employees in as partners in the business– silent partners, but all the same they found themselves with more of an interest in the operation than mere paycheque collection.

In 2006, Manfred Lamy retired from the head of the company, which means that like so many before it, it is no longer a family enterprise. There has however been no evident overturning of the underlying attitutes which have served the company over the decades, and looks set to persist for the forseeable future.

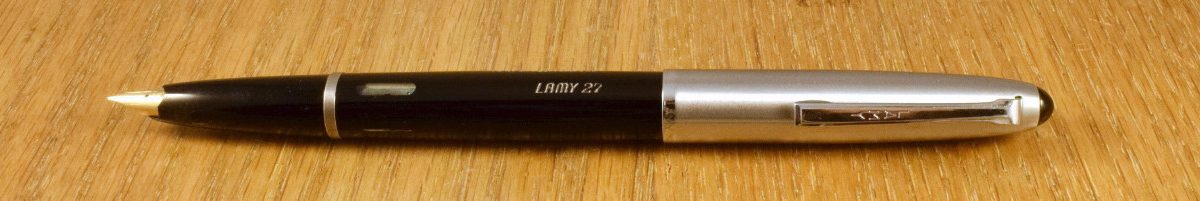

From 1952, with the introduction of the Lamy 27, the company has persistently occupied an avant-garde position in terms of design, using modernist rather than traditional body shapes. This modernism can be either utilitarian or whimsical, but there is a certain Lamy-ness to all the products and perhaps more than any other company one tends to see family traits in Lamy’s pens, or at least those made since 1966. A look at their website is something like a visit to a gallery of modern consumer design.

Models I’ve examined:

| Alphabetically | By Date |